My experiences with crisis pregnancies have made me adamantly pro-life, with a perspective I could never have imagined. I got pregnant at 16 by my 18 year old boyfriend when I ran away from home; I got life-threateningly pregnant again at 22 by my abusive addict boyfriend; and I got pregnant at 24 by a rape. In each case, there were people telling me what a wise choice abortion would be for me, what a compassionate choice for the child.

I have since been told that should I get pregnant again, the high risk clinic at the local hospital will recommend abortion, for my own safety. And yet, I am totally opposed to exceptions for rape and incest in pro-life laws and exceptions for ”maternal health,” which is so broadly defined under current case law it can mean anything.

My story demonstrates that all lives have value and meaning and deserve legal protection of their inherent right to live, no matter the circumstances. It also shows the necessity of building a culture in which women and girls in crisis are not pushed to abort as the supposed solution to their problems.

When I got pregnant as a teenager, I was in shock. I thought, naively, that what my boyfriend and I were doing was enough to prevent it. I was raised Catholic, and I knew what abortion was in the clinical sense, so it was unthinkable, and I eventually agreed to place the baby for adoption rather than parent. It was agonizing from the beginning to think one day I would be giving her to another family, but I wanted her to have the best in life, things I wouldn’t be able to provide. Her adoptive parents talked to me on the phone regularly and I felt comfortable with who they were, and that they would be good parents. I just wished I could be the one to be a mother to my precious girl.

The thought of giving her up was tearing me apart but the pregnancy did not proceed normally. I ended up in the hospital for weeks, on bed rest, trying to prevent a very premature birth. I had the chance to watch my little girl grow via ultrasound: I saw her heart beating, I saw her sucking her thumb and playing with her toes, and I saw her hair like a halo around her head.

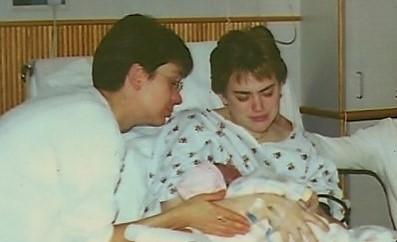

Ironically, I made it to full term before tragedy struck in an unexpected way. My daughter Lillian Mary was stillborn because of a cord accident. I would have given anything, I would still give anything, for her to open her eyes or grasp my finger, even for a moment. But I had the chance to love her and know her in the womb. If I had aborted her to stay in school, like some of my friends recommended, I would have missed having her in my life. I would never have known how beautiful she was, or held her perfect body, wrapped in hospital blankets, in my arms. I could never have seen her face in my nieces.

At least I had the chance to hold her and see her face. . . .

With my son Gaven Joseph, I was not so fortunate. The pregnancy was rough from the beginning. I went to a high risk clinic in Pittsburgh and the doctors and social workers there strongly suggested that I ought to abort, considering my psychosocial risk factors in addition to the physical risk factors. The baby’s father was an alcoholic, an addict, and abusive, and the high risk clinic knew it. I was working with a social worker on plans to safely leave him once my son was born. Physically, there were things that required monitoring but as the pregnancy progressed, they appeared to resolve. . . , until I reached 22 weeks and became extremely sick with a respiratory infection.

I was hospitalized in Pittsburgh and I had finally started improving. I had just moved out of intensive care when I felt a terrible pain, and saw something even worse: blood. My nurse called the doctor on call on my floor. After performing an urgent bedside ultrasound, they determined two things: my son was alive, but I had a placental abruption which was causing the bleeding. The doctor on the unit told me not to panic, that the tear was minor, and that the OB/GYN doctors saw these all the time and could handle it.

I was hopeful at that point, because if they could just keep me pregnant a couple more weeks, my son’s chances of survival were good. But when the OB got there, that all changed. She said they would be doing a D&E immediately — which I knew was an abortion procedure, because not only was there an abruption, my blood pressure had risen to a point she considered to be preeclampsia, which could only be cured by delivery.

I protested, knowing that my son was still alive, that the tear of my placenta was minor, that my blood pressure could be lowered by medication, that I could remain on bed rest, and that there was no way I would consent to a D&E. She countered that they wouldn’t be doing any of those treatment options, but if I objected so strongly to a dilation and evacuation — ripping my baby apart limb by limb, she would “induce” me instead.

It was early in the morning, by parents weren’t there, and I felt bullied. I had no advocate there, and I didn’t know what to do. I naively hoped to force them to provide life-saving care to my son if he survived labor and delivery. At the very least, if the doctors refused care like this doctor was doing, he would die in my arms, knowing he was loved, rather than being ripped to pieces.

But it became a moot point. They induced me, I went into labor, and everything went terribly wrong. The placental abruption completely tore, setting off a cascade of bleeding, shock, and inability to clot. I hemorrhaged my life away, as I was in shock and respiratory failure. I had a near-death experience where I saw my son and my daughter with the white bright light, running together. I wanted to go with them, but it wasn’t my time.

My parents had arrived at the hospital later that morning and were there to tell me it was time to allow the doctors to take my son via an emergency D&E, or even a hysterectomy to stop the bleeding, to try to save my life. At the last ultrasound done to check on the placental abruption, my son was still alive. But things had gotten much worse and I didn’t know if he was still alive or not, and I wasn’t in a great state in being able to make decisions. I didn’t want to live at my son’s expense; in fact, at that point I wanted to die with him rather than be responsible for his death.

I refused and refused to sign the consent. I could not help but wonder if they had done what I’d asked them to do for treatment instead of inducing labor, maybe I wouldn’t be in this position now. I’d totally lost trust in these physicians.

My parents reminded me that the intent was not to kill my son but to try to save me. They strongly felt I had a moral obligation to try to live, that it was not morally acceptable to choose to die with my son. They saw it as equivalent to committing suicide. Reluctantly, I signed the papers. I consented.

I found out later that the doctors didn’t give me much of a chance to live: as soon as I signed the papers, they actually ran down the hall to the OR. They didn’t even give my parents a chance to say goodbye, much less to call a priest to give me the last rites, and my family called all of our connections with the simple message “Megan is dying, please pray.”

I survived, but even to this day, I feel guilty for it. I would have died for my son, but he died for me instead.

After I lost my son, I moved back to Michigan and eventually recovered enough to try to go back to church. That didn’t work out so well for me. I was raped in February, 2007 by someone I knew from a young adult group at my parish, on the anniversary of my daughter’s funeral. He was a friend, I thought, someone I could trust and talk to about Lillian and about my feelings of alienation because of the loss of my son. That trust was misplaced.

I went to the hospital, reported the rape to the police, and four counts of 1st degree criminal sexual conduct charges were filed.

At the hospital, a volunteer counselor from the local rape crisis center met me and walked me through the ordeal of filing a police report and being examined by a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner. I am glad someone was there to help me get through it, because it was incredibly humiliating and in the immediate aftermath of being raped, even a female nurse examining me was traumatizing. And . . . , the pictures she had to take felt shameful, since I knew they would be seen at least by the police and the prosecutor and possibly by a jury and more. The crisis center helped me obtain a personal protective order as well, when the rapist began to harass me in between the police report and his arrest.

As I was preparing for the preliminary hearing, I found out I was pregnant from the rape. I got in for an emergency counseling appointment because I was completely overwhelmed. I was shocked, horrified, shaking, vacillating between wanting to keep the baby I barely knew was there and being concerned I would hate him if he were a boy and looked like my rapist. I was a mess and I needed to talk to someone who dealt with this sort of situation.

But . . . , my counselor’s response was to tell me that since I’d been raped, Medicaid would cover “the procedure” at the Planned Parenthood in town and I could get in right away since the crisis center worked with them. I was astonished that she didn’t ask how I felt about being pregnant, or what I wanted to do, but just offered me an immediate abortion as though that would fix something.

I was already so conflicted about being pregnant by a violent act, and here was the solution being proposed: stick metal instruments into my already violated body and rip that baby right out, like that will fix it. No, it would not!

I had already been through the violation of the induction and subsequent violent D & E with my son Gaven Joseph, to save my life. Subjecting myself to a surgical procedure to end the life of this child would be physically painful, emotionally destructive, and gravely wrong. And it wouldn’t wipe away the rape. I couldn’t blame my baby for how he or she came to be. I couldn’t think of my child as “my rapist’s son” or as “that evil man’s daughter.” Whoever he or she would be, their father’s sins and crimes were not theirs. My child was innocent.

But I never got the chance to know who that child would be. After being on the stand all day at the preliminary hearing in the rape case, I began to bleed. I knew what was probably happening, but I went in for a blood test and my hormone levels had dropped to nothing. I miscarried my 10-week baby at home. It was painful, traumatic, and terribly sad, holding my baby’s remains in the tissue. My baby wasn’t tissue, but recognizably human! Anyone who has had a miscarriage at that stage knows what I mean.

My trip to the ER during the miscarriage made a bad situation worse. I had a friend drive me because I was in such bad shape. She held my hand during the heartbreaking ultrasound and talked to me as I received IV fluids and blood products to counter the hemorrhage. Finally the OB resident came in and informed me, “Your body has done such a good job cleaning itself out, it spared you the trouble of getting rid of it later.”

That’s a direct quote I can’t forget. The miscarriage spared me the trouble of an abortion? The breathtaking arrogance, the lack of compassion, the presumption that because I was raped my child meant nothing to me, just enraged me and I told that resident in no uncertain terms exactly what I thought of him.

My crisis counselor and my ER doctor made the common assumption, as it turns out: if a woman finds herself pregnant by rape, obviously she will, and even should, abort. Likewise, if a woman in an abusive relationship gets pregnant, the best thing for her, and even for her child, is to have an abortion. After all, how could she possibly bring a child into such a situation? And teens certainly shouldn’t try to parent, and giving the baby up for adoption is too hard, and the baby’s fate too uncertain: best to abort. . . , so they say.

I see it online in comments on articles and on social media, I hear it on talk radio, I read it in columns. even from otherwise pro-life people: “Yes, it’s a life, but I could never force my daughter to carry a rapist’s baby.” Or, “A blanket ban on abortion isn’t politically feasible, an incremental approach is better; exceptions must be made.”

Rape is an act of violence. It violates the body, the heart, and the soul of the survivor. Abuse by someone beloved is another act of violation, not only against the body, but the heart and soul of the survivor. Abortion is yet more violence. It, too, violates the body, heart, and soul of the victims, mother and child. How can anyone make the case that violation is the solution to violation, violence the solution to violence? Allowing the killing of babies who result from rape is not healing; nor will terminating the lives of babies of abuse survivors be freeing.

No woman in crisis needs abortion to save her. Every innocent child deserves the chance to live. We can do better as a society, and especially as pro-life people, at loving and supporting these women and their children no matter what the circumstances may be.

BIO: Megan Mishler is the oldest of 7, resides in Michigan and is a pro-life blogger for Save The 1. She is passionate about post-abortion recovery and ministries.